AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND ASSOCIATION FOR

BIBLICAL STUDIES

Postgraduate Conference, 2018

31 August, 2018, 9am-4pm

The University of Auckland

Arts 1 building, 14A Symonds Street, room 203

The inaugural postgraduate conference of ANZABS takes place on 31 August, 2018. The conference will be held at the University of Auckland, Arts 1, 14A Symonds Street, room 203 (you’ll find Arts 1 on the City campus map). As you will see below, we have a fabulous line-up of PG students from Aotearoa NZ and beyond whose research spans biblical studies, religious studies, cultural studies, and theology.

The conference is free and open to everyone. We will provide tea and coffee for morning and afternoon tea (and some cookies, although you are welcome to contribute too!). Lunch will be a ‘get-your-own’ affair, and there are lots of food vendors around campus, as well as a kitchen in Arts 1 (in case anyone brings their own).

If you are keen to come along to listen to our speakers, please drop a note to Caroline Blyth. And please share this invitation widely among your networks.

Programme

9.00 Mihi

9.10 – Ben Hudson, Otago: Ephesians’ Jewish Readers

9.40 – Karen Taylor, University of Chester: Cutting judgment in pieces: a judgment parable through a lens of relational faithfulness.

10.10 – Marina Pasichnik, University of Auckland: Descent into Hell in Russian Iconography

10.40 – Morning Tea

11.00 – Anne Aalbers, University of Auckland: The Ascetic Couple

11.30 – Paul Mosley, Laidlaw College: Paul and Adversity

12.00 – Therese Kiely, University of Auckland: Young Pasifika women’s images of God and mental wellbeing.

12.30 – (Get your own) lunch

1.30 – Lyndon Drake, Oxford University: Economic Capital in the Hebrew Bible.

2.00 – Taryn Dryfhout, Laidaw College: Kaumātua ahi kā; Kaumātua ahi tere: Considering a theology of adoption and how it relates to the Māori practice of whāngai.

2.30 – Tekweni Chataira, Laidlaw College: Motive and Intent in the Book of Ruth: A Narrative Critical Interrogation of Naomi.

3.00 – afternoon tea

3.30 – Caroline Blyth, University of Auckland: Reflections and Q&A on the PhD journey

4.00 – Farewells

Abstracts

Ben Hudson, University of Otago: Ephesians’ Jewish Readers

Ephesians presents its interpreters with numerous puzzles, not only over questions of authorship, but also audience, setting, and purpose. In a number of places, Ephesians identifies its addressees as Gentiles (2:11, 3:1, 4:17), and for this reason most interpreters assume that the intended audience of the letter are essentially Gentile believers. This paper will argue, however, that Ephesians was intended to be read as well by Jewish believers, and that this has implications for discerning its purpose and setting.

A number of features of the letter point to this conclusion, including: prominent Jewish literary characteristics; the reciprocal manner in which unity between Jews and Gentiles in the church is promoted; the use of οἱ ἅγιοι (‘the Saints’) as a designation; the way Paul himself is portrayed; and Ephesians’ distinctive ethical material.

These elements suggest a rhetorical strategy in which Jews are addressed in Ephesians, not as Paul speaks to them directly, but in hearing Paul speak as a Jew and on behalf of Jews to Gentiles. Furthermore, they point to a Sitz im Leben and purpose in which the letter aims to bring Jewish believers into the orbit of pauline churches.

Karen Davinia Taylor, St John’s College Nottingham & University of Chester: Cutting judgment in pieces: a judgment parable through a lens of relational faithfulness

David Ford has argued for a wisdom hermeneutic as “engagement with scripture whose primary desire is for the wisdom of God in life now,” nurturing wisdom’s childlike openness to surprise (Ford, 2007, 52). The desire to grow such wisdom within a multi-ethnic congregation motivates this fresh interpretation of Matthew 24:45-51.

Scholarship situates this parable of the faithful or unfaithful slave in an eschatological discourse. Within that, the phrases “cut in pieces” and “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (v. 51) are heard as guilty sentences, meted metaphorically or literally, resulting in torment, even repentance (Erdey & Smith, 2013; Sim, 2002; Snodgrass, 2008). In dialogue with scripture, experience and biblical scholarship, including 1 Samuel 24: 5-8 (Gordon, 1990), I argue for a lens of relational accountability where Jesus describes daily social dynamics. And while this shapes eternal life, the focus of this wisdom hermeneutic is on human flourishing in life now. This paper reads the parable as teaching how to live well while we wait for Christ’s return. Such a voice aims to be gentle, robustly curious and respectful of multiple conversation partners in its 21st century context.

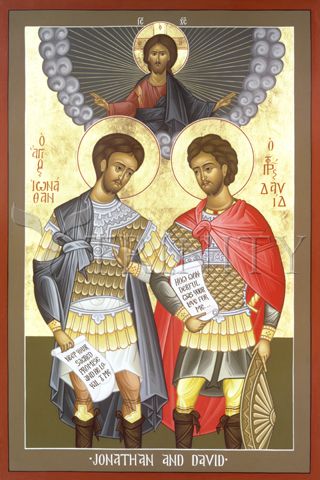

Marina Pasichnik, University of Auckland: Descent into Hell in Russian Iconography

This presentation will examine features of change in the depiction of Eve in medieval Russian Descent into Hell icons. Eve’s physical characteristics and her proximity to Christ’s mandorla in these icons carry symbolic and eschatological meaning because Eve was the prototype of women. The changes in the icons will be discussed in relation to the Neoplatonic and Hesychastic spirituality that underpinned Russian Orthodoxy at this time. The increased reverence that the Hesychasts had for the Virgin Mary raised the status of Eve too as a prefiguration of Mary. The salvation message of these icons extends beyond their time with implications for both the role of Eve and Mary at the end of time when humanity is judged.

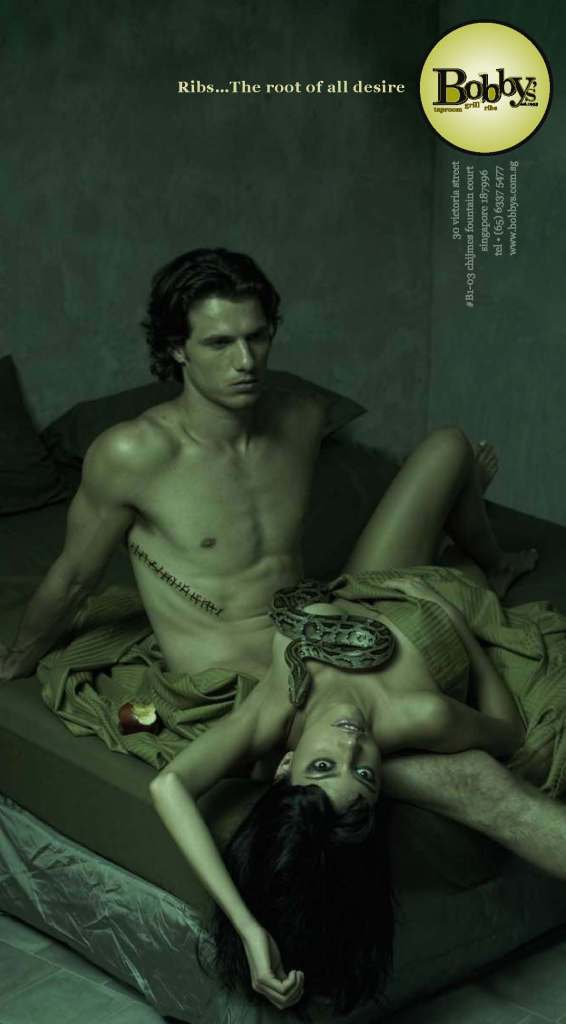

Annie Aalbers, University of Auckland: The Ascetic Couple

There is little we know about Mary Magdalene from the New Testament. Although she was a very significant woman – mentioned in all four Gospels at the significant points in Jesus’ life and central as a witness to the resurrection – she only features there as the woman in Jesus’ entourage healed of seven demons and in the post-resurrection encounter in John 20:11-18. In the Nag Hammadi Library and apocryphal works in general, however, she plays a role as a counterpart to Jesus as a leading ascetic. This paper will examine Mary’s role in several of these texts and, based on that, suggest some implications for understanding her role in John 20:17. There, the prohibition to touch directed by the resurrected Jesus to her, has puzzled many a scholar, but gains some clarity in the context of such asceticism.

Paul Mosley, Laidlaw: Paul and Adversity

This study investigates Paul’s understandings of adversity, to answer the question: does Paul provide practical theodicies that might help modern-day Christians deal with adversity? The study considers nearly sixty passages from eleven of Paul’s letters; it is a broad and exploratory survey.

Paul does not provide explicit teaching on adversity, but most of his references to it are intended to inform, encourage, and guide the reader. His wide-ranging understandings of the nature of adversity can be expressed as a set of theodicies (both practical and explanatory), which I have called Primordial Sin, Normal Christian Life, Christian Ministry, Gift of God, Spiritual Opposition, “Bad Choice,” Eschatological Recompense, Retribution, and Educative and Discipling Theodicies. There are some commonalities with Jewish/OT and Hellenistic thought, but Paul develops his own understandings. Thus, the Pauline Retribution Theodicy is similar to the Jewish equivalent, but Paul sees retribution as applying to non-believers (who have rejected the gospel of Christ), rather than the people of God (who have received Christ and are assured of eternal salvation, although they may continue to do wrong).

Paul’s responses to adversity also are wide-ranging: trust and depend on God, draw on the Holy Spirit’s resources, be disciplined, learn from adversity, maintain unity, make right choices, pray, rejoice, do not take revenge, actively confront adversaries, and seek the progress of the gospel.

Modern “popular” Christian literature on adversity shows both similarities with and significant differences from Paul’s understandings. There is emphasis on the educative and discipling benefits of adversity, and on the concept of God’s “perfect plan” for the believer’s life. The first is very Pauline. The second seems to conceive God as directing every detail of one’s life, which differs from Paul’s certainty that God is engaged in the believer’s life, can turn any circumstance to good, but does not plan and direct every eventuality nor set aside human ability to make choices. On the other hand, there is little reference in modern “popular” literature to Paul’s belief that Christians experience adversity simply because as Christians they threaten non-Christian society, or to his foundational expectation of an eternal reward on the day of Christ.

A particular concern of modern western Christians is illness, about which Paul has remarkably little to say. He never mentions it as a hardship that validates his apostolic ministry; Epaphroditus’s illness caused him great anguish; and he regarded the illness and death of some Corinthians as regrettable but necessary discipline. On the other hand, he recognizes healing as a spiritual gift that he himself uses. We may conclude that Paul sees no benefit in illness (the case of the Corinthians is an explicable exception). It should be confronted by prayer and the gift of healing, in the confidence that God, too, does not favour illness.

There are differences between the circumstances in which Paul wrote his letters and in which modern western Christians live. Nevertheless, the divergences between Paul’s understandings of adversity and those of modern western writers suggest that reflection on the influence of modern and postmodern worldviews on our understandings of adversity is warranted.

Therese Kiely, University of Auckland“But who do you say I am?” Images of God and NZ-Pacific Mental Wellbeing

My research investigates the significance of Christianity for the spiritual and mental wellbeing of young Christian, multi-ethnic Pacific women. It focuses on this cohort’s individual images of God, what influences these images of God and how these images can impact an individual’s mental wellbeing. Roman Catholicism, mixed ethnic cultural backgrounds, family life and social media all intersect in discerning who God is for these young women and how they see themselves in the world. Using the Praxis Model and an Intersectionality hermeneutic, I aim to weave strands together and contribute to community suicide prevention strategies.

Lyndon Drake, Oxford University: Economic Capital in the Hebrew Bible

Abstract to follow.

Taryn Dryfhout, Laidlaw: Kaumātua ahi kā; Kaumātua ahi tere: Considering a theology of adoption and how it relates to the Māori practice of whāngai

Tikanga plays a significant role in the Māori world, and in New Zealand society, due to the unique status of Māori as tangata whenua, and as partners of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In particular, Māori cultural ideas about whanau (family), whanaungatanga (relationships), and whakapapa (genealogy), have come to shape many Māori practices, including the long-established institution of whāngai. The purpose of this research was to gain insight into the practice of whāngai, and how this might relate to a theology of adoption. This began by exploring Māori understandings of the practice of whāngai, looking at how both whāngai and adoption has been, and currently is, practiced in Aotearoa, and comparing how whāngai differs from western understandings of adoption. This revealed that whāngai operates out of the principle of whanaungatanga – relationship, kinship, family connections. This kinship principle is what shapes the beliefs, attitudes and motivations for whāngai. Biblical investigation into Pauline adoption revealed a similar thread. Paul’s adoption metaphor draws on the kinship language that is pervasive throughout Ancient Israel and the Old Testament to shape and express the way in which believers are adopted into God’s family, locating a theology of adoption within the wider ideas of family, and kinship. As a result, several connections can be drawn between a theology of adoption, and contemporary whāngai practice including the shared concern and reverence for genealogies and whakapapa, the emphasis on family and community, and the shared language of kinship. Paul draws on ideas of kinship from the Old Testament in order to construct his metaphor for adoption. In the same way, whāngai is deeply bound up with the kinship framework and the wider principal of whanaungatanga which places value on family processes, kinship obligations and the concern for the collective, over the individual. It within this rich kinship framework that whāngai can be understood as a practice, and theologically.

Tekweni Chataira, Laidlaw: Motive and Intent in the Book of Ruth: A Narrative Critical Interrogation of Naomi

There has been recent debate amongst Book of Ruth scholars concerning Naomi’s relationship with Ruth. Phylis Trible, in God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality, holds a majority view that Naomi was a grieving widow and had only the best of intentions for her daughters-in-law, Ruth and Orpah. Fewell and Gunn hold a provocative view contrary to Trible. In their article “A Son is born to Naomi,” contra Trible, they assert that Naomi displays mixed motives and that her concern for her daughters-in-law is superficial, and further, that her later interaction with Ruth is opportunistic rather than altruistic. Fewell and Gunn’s views are, in part, based on their reading of the gaps and ambiguities (silences) as well as literary allusions in the narrative with regards to Naomi’s underlying agenda. Since the publication of the Fewell and Gunn article, there has been a great deal of interest in this conversation.

This study is an exploration of motive in Naomi’s relationship with her Moabite daughters-in-law, especially Ruth. Through a detailed narrative analysis of key scenes involving both Naomi and Ruth, this study explores Naomi’s and Ruth’s relationship keeping the scholarly debate in mind. Narrative analysis provides a further evaluation of the text in this light and contributes to the scholarly discussion concerning Naomi’s intentions towards Ruth. Engaging in this conversation is a chance not only to acknowledge and understand the presence of different views about the characters in the text but also to evaluate them.